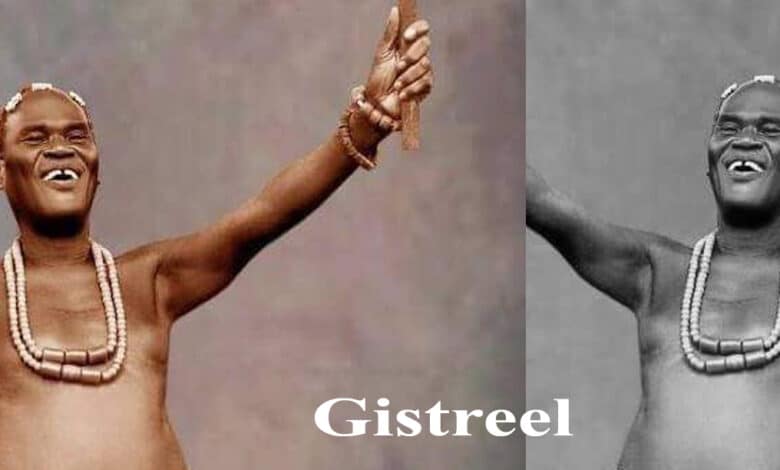

Hubert Ogunde Biography

Hubert Ogunde was a magical character to many older Nigerians who knew him as an actor, theatre manager and playwright, musician, folklorist, policeman and teacher, activist and nationalist.

Some who knew him remember him affectionately as the father of Nigerian theatre, a claim that, although genuine, does not reflect the authenticity of his legacy as one of Nigeria’s founding fathers.

Hubert Ogunde Biography

Hubert Ogunde was born to Jeremiah Dehinbo and Eunice Owatusan Ogunde in 1916 in Ososa, near Ijebu-Ode, Ogun State. He began performing as a dancer and percussionist alongside Egun Alarinjo, Dara Mojo Atete, and Ekun Oko as early as 1924 when he was eight years old.

From 1925 to 1928, he attended St John’s School in Ososa for his elementary education. From 1928 to 1930, he attended St Peter’s Faji School in Lagos, and from 1931 to 1932, he attended Wasimi African School in Ijebu-Ode, where he became a teacher and organist.

He joined the Nigerian Police Force in 1941 at the age of twenty-five (25) and was sent to training at the Police Training School, Enugu from March to September, after which he was posted to Ibadan in October as a third-class constable, in 1943 he was transferred to Nigerian Police Force ‘c’ division Ebutte-Metta, Lagos.

Hubert Ogunde Theatrical Beginning

Ogunde eventually quit the police force in 1946 to pursue a career in the theatre. He had been exposed as a child to the Yoruba travelling theatre, ‘Alarinjo,’ as well as masquerade performances during festivals.

Hubert Ogunde’s career as a dramatist and entertainer benefited greatly from his knowledge of traditional practices gained through his background, his familiarity with the Bible, and successful plays that had been sponsored by the church early in his career.

Professor Ebun Clark, his biographer, stated that ‘one of Ogunde’s significant contributions to the history of professional theatre in Nigeria is that he took the theatre from the direct patronage of court and church and delivered it to the people.’

As a theatre pioneer in Nigeria, Ogunde encountered numerous problems, including recruiting actors and making money from theatre.

The first issue stemmed from the conservative nature of the community.

Entertainers were regarded as unprofessional by Nigeria’s increasingly educated middle class; also, Hubert Ogunde had to persuade an audience accustomed to free masquerade acts to pay for performances.

Nonetheless, he overcame these obstacles and established the African Music Research Party in 1945 to recruit players and stage plays around the country.

Hubert Ogunde Political Career

Hubert Ogunde began putting up plays and travelling throughout Nigeria. He gradually moved away from performing plays with Christian themes and began tackling broader, current topics.

He also began an extended travelling schedule that carried him to Nigeria’s hinterlands. This was the moment of nationalism, and Ogunde’s theatre was thoroughly immersed in it.

In his plays, he would frequently address societal issues, working alongside nationalists such as Samuel Akisanya and Ernest Ikoli, using entertainment as his own vehicle for emancipation.

According to Ebun Clark, Hubert Ogunde created plays “to instil cultural pride in Nigerians so that they can realize that colonial rule had to end.” His extended travels throughout Nigeria also led to his final conception of Nigeria as a unified state.

Future Nigerian President Nnamdi Azikiwe presided over the opening of his play ‘Worse than Crime’ in 1945. The act demonstrated to the audience that colonialism was worse than normal offences that society openly punished.

In October 1946, Ogunde was detained in Jos after police dispersed a performance of ‘Strike and Hunger,’ a play on Nigeria’s 1945 general strike, which paralyzed numerous industries and enraged the colonial government.

He also performed ‘Bread and Bullet,’ a dramatization of the 1949 Iva Valley shooting.

Ogunde’s work as an artist supplemented the nationalist efforts of politicians, journalists, and activists. He continued to stage plays about current events, and his authority over the masses alarmed the colonial rulers.

Through his theatre, he travelled across Nigeria, conveying his idea of what the new nation should be. He had access to the masses and blended amusement and political instruction, prompting the colonial rulers to censor him multiple times.

Ogunde, like the other nationalists, used the local press to defend himself whenever he was harassed by the authorities, and the local press backed him up.

Ogunde and Awolowo

In his theatre ensemble, Ogunde frequently portrayed many parts. In addition to his roles as artistic director, dance choreographer, and author, he used to drive the tour bus.

In 1970, one of his wives, Adeshewa, who also doubled as a lead actress in the company, died in an accident on the way to a performance in Ilesha. Ogunde married 17 wives and produced more than 20 children, all of whom were active members of the troupe in various capacities, just like his wife.

Ogunde was commissioned to create a play commemorating Nigeria’s independence after the nationalistic phase of the 1940s and 1950s. ‘Song of Unity’ was first performed at Glover Hall in 1960.

The Western Region was in crisis a few years after independence due to disputes between the premier, Chief Samuel Ladoke Akintola, and his predecessor and party head, Chief Obafemi Awolowo.

Several Nigerians associated with their ethnic groupings rather than British-constructed Nigeria at the time and several political parties were created along ethnic lines.

Political parties were also expected to have a cultural wing. Ogunde publicly respected Chief Obafemi Awolowo, the leader of the Action Group, Egbé m Odùduwà.

Chief Ladoke Akintola commissioned Ogunde to create a play for Egbe Omo Olofin, the cultural arm of the newly reconstituted Nigerian National Democratic Party.

Ogunde, like many Yorubas, supported Awolowo, who was imprisoned by the Federal Government in 1963 on treason charges.

On February 28, 1964, Ogunde sang ‘Yoruba Ronu’ at Ibadan’s Obisesan Hall. ‘Yoruba Ronu’ alludes to the events that led to Akintola and Awolowo’s feud.

The play told the story of a good king who was betrayed by his deputy, echoing public views about the Western Region’s continuing turmoil.

The treacherous deputy was eventually shamed and executed in the play. Chief Akintola was present at the premiere of the play and was scandalized, marching out of the hall with some of his ministers.

Ogunde was barred from performing in the Western Region the next day.

Also Read A.A Rano Net Worth and Biography 2023

His music and plays were also barred from being broadcast on the government-owned Western Nigerian Broadcasting Services throughout the embargo period.

When Akintola was slain in a failed coup attempt that led to a military takeover of power across the country, Ogunde’s prophesy in the play came true.

This was not Ogunde’s first time being censored, but it was the longest censorship he had ever endured. The prohibition was subsequently lifted after Ogunde petitioned the newly formed Western Region military administration.

His success in getting the embargo lifted could be attributed to his friendly relationship with Awolowo, who was released from prison and appointed federal minister of finance by the military head of state.

The International Ogunde

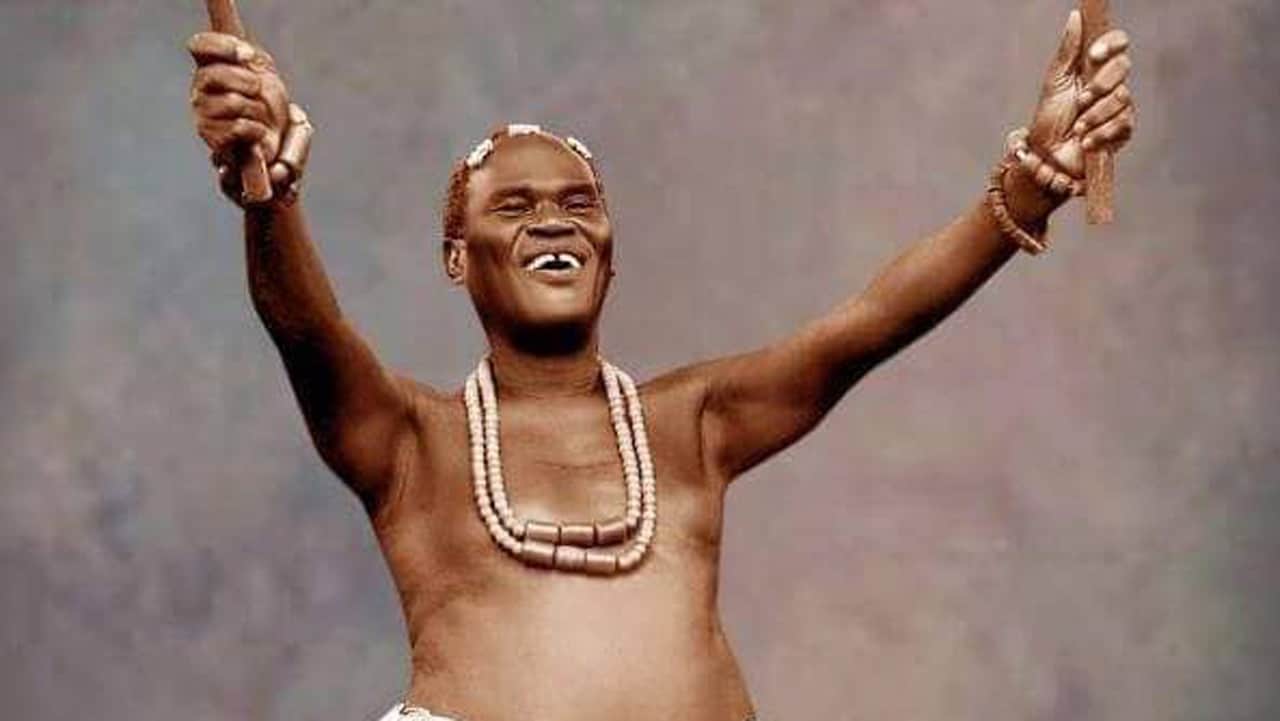

Ogunde was cosmopolitan, but he maintained his primary identity as a Yoruba.

His theater incorporated aspects from several civilizations from both within and outside the country. He brought Nigerian culture to Europe, the United States, and other African countries. He has a number of successful tours around the world.

He played at the famed Apollo Theatre in Harlem, New York, after representing Nigeria at Expo 67 in Montreal, Canada.

Ogunde also mixed traditional and modern instruments. Surprisingly, he employed the agba drum, which is generally associated with the esoteric Ogboni sect and is not used for entertainment.

This prompted speculation about his involvement in the Ogboni cult, despite the fact that members were not permitted to use the drum for other purposes.

Ogunde is credited with demystifying the drum, which is being used by modern folk musicians. In his plays, he also included chants and folklore that were previously unknown to many people.

Hubert Ogunde was also a talented musician, although his popularity as a playwright makes it easy to overlook his songwriting.

His discography is listed as 97 recordings on the Ogunde Museum’s website. His voice, which alternated between bass and tenor, was recognizable and distinct.

The Father of Modern Day Theatre

While Ogunde is widely regarded as the founder of modern Nigerian theatre, his influence extends beyond the stage.

He was one of Nigeria’s founding fathers, and his legacy lives on in various forms in popular culture, memory, and modern imagination.

Nigerian theatre has gone through several stages, and the country’s film industry remains one of its most important cultural exports.

Ogunde’s pioneering efforts are responsible for Nollywood’s success both at home and internationally.

Some say Ogunde also played a role in the cultural revolution that transformed the old notion of Nigerian artists as layabouts.

Theatre might be organized like any other business to generate income, profit, and self-fulfilment.’ Ogunde turned his passion for entertainment into a full-time job and a successful career.

Hubert Ogunde’s brilliance was also evident in his ability to integrate influences in order to create theatre that was both local and global. Ogunde’s work was recognized for its syncretism, which finally became a regular feature in Nigeria’s film industry.

One of Ogunde’s contributions to Nigerian filmmaking has been the inclusion of herbalists and diviners in Nollywood stories.

Despite the fact that he did not make many films during his lifetime, Hubert Ogunde’s pioneering efforts in the profession inspired early filmmakers. He is regarded as an artist whose works reflected the politics of the day and continue to have something to say.

Songs he produced, for example, are still heard on Nigerian radio and television broadcasts. The title tune from his 1981 film, Jaiyesinmi, emerged in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic because it contains a prayer against pandemics.

Every time there is a controversy concerning the role of the Yoruba ethnic group within the wider Nigerian nation, his song ‘Yoruba Ronu’ (a cry for Yoruba unity) resurfaces.

‘Eko,’ a song he wrote about Lagos in 1974, is still considered one of the most important reflections on Lagos life.